Stenay - november 1914 - Armistice

History of the 353rd Infantry Regiment - 89th Division

By : History of the 353rd Infantry Regiment - 89th Division

NATIONAL ARMY USA - SEPTEMBER, 1917 - JUNE, 1919

The 12th of November, 1918, found the 353rd Infantry concentrated in Stenay. Since entering the Lucey Sector a hundred days before the men of the regiment had been sheltered in dugouts and fox-holes; now they occupied the homes of this French city

A summary of information had given these facts at the beginning of the advance on November 1st:

"Stenay, on the Meuse, sixteen kilometers southwest of Montmedy, 4,070 inhabitants, 598 houses, one mill, 200 wells, one nail factory, one sawmill, barracks for three artillery regiments, passenger and freight depots on the Sedan-Longwy railroad."

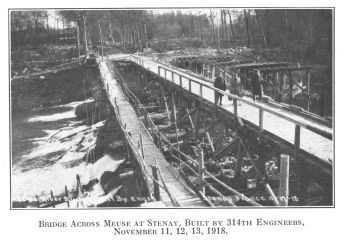

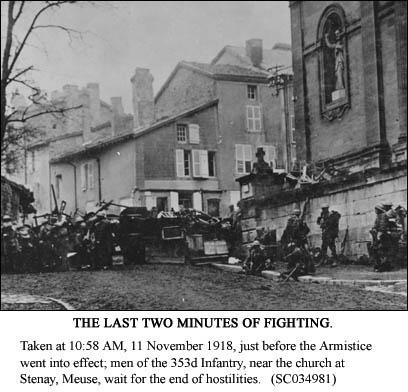

This statement was brief, but to those in Stenay who had advanced from shell hole to shell hole, wading marshes, and struggling through woods, it was the revelation of a task accomplished. The flooded Meuse was crossed. One line of the enemy's lateral communications, the Sedan-Longwy railroad, had been cut. The great American Objective--the Sedan-Mezieres railroad--was within grasp; the German forces were divided-the victory was won.

Only a few civilians remained in the city, mostly old people under the direction of the parish priest. They could scarcely believe the presence of the strange but kindly Americans. With a great deal of interest the soldiers gathered the story of their city. Stenay fell into the hands of the Germans in August, 1914, and was held by them until November 9, 1918, when, under the pressure of the American troops they evacuated the city.

Ten days before the armistice the civilians were given two hours to leave. This order synchronized closely with the advance of the Americans on November 1st. Moreover, one of the first prisoners captured by the 353rd Infantry on the morning of November 1st, said that he had just been sent up from the Replacement Camp at Stenay. These apparently inconsistent actions of the enemy were explained in the condition of the looted city. The irresistible advance of the Americans in the early days of November had warned him that his long occupation was nearly over. So he pushed up replacements to hold his lines and, at the same time, ordered the civilians out in order to make sure of his escape with the booty.

Viewed from the distance Stenay seemed to have escaped the fate of nearly all other French cities in the battle areas. American artillerymen had thrown their shells into the immediate vicinity but few if any into the city. The church, the most prominent of all the buildings, maintained its old time grandeur. The massive artillery barracks showed only the disorder of a hasty retreat; and the chateau where the crown prince had been quartered still retained its peaceful charm. Exceptions appeared along the river. Here the bridges had been blown up, and the flooded Meuse had scattered debris in every direction. A glance within the city told the true story. Every shop had been looted and only heaps of refuse were left behind. Streets had been barricaded with furniture and household equipment; the lighting and water systems were completely out of commission; sewerage mains were blocked, and many of the best homes had been used for offices and workshops. The most malicious example of wanton destruction appeared in the laboratories and home of M. Jaudin. According to the aged scholar's own statement, two German officers with a detail of soldiers appeared at the last moment and smashed test tubes and apparatus and then entered the living rooms and tore the curtains from the walls. Even the treasured letters of a lifetime were destroyed before their eyes. Nor had the church, so grand in the distance, escaped pillage. The pipes of the organ had been carried away to German munition factories to be moulded into shells.

These revelations shocked the Americans, but they were none the less surprised at the fine spirit of the returning refugees. Gradually and almost timidly they came to ask shelter and peace in their own homes. What sights greeted them--empty rooms, marred walls and ruined floors. But the sympathetic and hearty welcome of the Americans seemed to inspire them with new hope. Promptly and cheerfully they began life over again; some moved directly to places where they had concealed a few heirlooms from the invaders. A French lady dug up her silverware in the backyard. An officer who had been the town recorder before the war, pried up the stones of a basement floor and took out the city records. The greatest surprise of all was the sudden appearance of the Tri-Color from every house occupied by Frenchmen. Though stripped of possessions and humiliated by invaders, the traditions of the city, her spirit and patriotism, were stronger than ever.

The situation, however, demanded immediate action. Company "G" was detailed to post the first guard and each organization moved into its quarters. The men needed no urging to make themselves comfortable. Within a day every man had "made arrangement" for a stove and a bed and then came the traditional order, doubly emphatic in the 353rd Infantry, "Police Up!" Floors were scrubbed, backyards cleaned, streets swept and trash wagons put into ceaseless motion. Parties were sent out to bury the dead horses. Following the police order came inspections by platoon commanders, company commanders, regimental and higher commanders, and within a week the devastated and deserted city was a well regulated garrison.

The situation, however, demanded immediate action. Company "G" was detailed to post the first guard and each organization moved into its quarters. The men needed no urging to make themselves comfortable. Within a day every man had "made arrangement" for a stove and a bed and then came the traditional order, doubly emphatic in the 353rd Infantry, "Police Up!" Floors were scrubbed, backyards cleaned, streets swept and trash wagons put into ceaseless motion. Parties were sent out to bury the dead horses. Following the police order came inspections by platoon commanders, company commanders, regimental and higher commanders, and within a week the devastated and deserted city was a well regulated garrison.

Of equal importance to this general police was the personal clean-up and re-equipment of the men. A new drive was on-this time against the cooties. They were strongly entrenched and the greatest difficulty seemed to be in their unlimited replacements. Change of clothing was imperative and so the surplus kits that had been left back at Transvaal Farm and in Bantheville Woods on November 1st had to be gathered up. The Regimental Supply Company beat all records for service. New suits replaced the ones that had been through the drives; underwear and socks were abundant; new shoes replaced for old ones. These shoes were mostly of English manufacture and not well suited to the feet of American doughboys. They were large enough but seemed to take no account of the difference in shape of an individual's feet.

For the time it was a good joke on Tommy. "Odd, ain't it that 'e should 'ave both feet alike?" remarked a Yank as he walked out in a new pair of the heavy, box-toed, iron-capped boots. But the comedy changed to tragedy later. Rations, too, were generous. With new equipment, beds, to sleep in, mail from home, regular meals, and best of all, the hope of an early return to the "Good Old U. S. A.," the men rapidly came back to oldtime form. And when General Sommerall, the corps commander, came to express his admiration for the fighters he added a strong commendation for the soldiers of the 353rd Infantry.

From some unknown source appeared a rumor about assignment to the Army of Occupation. This new duty was supposed to be attractive: first, it was an acknowledgment of efficiency; second, it afforded an opportunity to see Germany. The general feeling however, among the men was--"The war is over, I want to go home." Private Trigg argued, "I joined the war, not the army, I want to get back in time to put in a crop next spring." To the American soldier the white flag of the enemy meant the end of the scrap. The miserable task was done, he was anxious to take up life where he had left off when his number was called. During campaign days he gladly put his last ounce of energy into the struggle, scorning even the suggestion of a halt until the victory was his, but it had not occurred to him that there was still danger of losing the fruit of victory even after the victory was won.

Because the American soldier considers the maneuvers and issues of battle it is not to be inferred that he hesitates in obedience. When the Training Schedule for the week beginning November 18th appeared, drill took on the "snap" of preparatory days:

First Call, 6 :00 a. m.

Assembly, 6:10 a. m.

Reveille, 6:15 a. m.

Reveille, 6:15 a. m.

Mess, 6:30 a. m.

Inspection, 8:00 a. m.

The schedule continued with setting-up exercises, close order drill and guard duty. "Lectures under the supervision of company commanders on pertinent historical and military subjects," were included; and, in addition, paragraph "B" provided "daily classes in the French language, compulsory for all officers, and recommended in each company for enlisted men." Finally, what seemed most portentous of all, was this requirement: "Practice march of at least twenty-four kilometers under full mobile equipment." Before the schedule was well under way, orders were received to begin the construction of a target range; and soon one battalion was detailed each day to repair roads; the Third Battalion had already marched to Margut to receive returning prisoners of war and to take over enemy property. Surely, there was enough to do for the 353rd Infantry in Stenay.

Suddenly all activities were suspended. An order came from Regimental Headquarters requiring "All officers report at once." Colonel Reeves announced that the 89th Division was to form a part of the Army of Occupation, and read the following order.

From: Illustrious I. P. C. Stenay.

To: C. O. 353rd Infantry.

Hour: 12:00. Date, 11-22-18.

The forward movement will begin the morning of 24th November. No effort will be spared to prepare for it. Immediate report will be made to these headquarters by phone of approximate shortages of equipment. Inspections will begin at once and accurate report of shortages will be made to Immortal I through these headquarters. All training and work on target ranges will be subordinated to preparation and equipment.

Signed: ILLUSTRIOUS I.

Recd. 12:15. By DAVIS.

November 24, 1918, came on Sunday, the regular moving day for the regiment.

NATIONAL ARMY USA - SEPTEMBER, 1917 - JUNE, 1919

CAPT. CHARLES F. DIENST -Historian 353rd Infantry

FIRST LIEUT. CLIFFORD CHALMER - Historian First Battalion

FIRST LIEUT. FRANCIS M. MORGAN - Historian Second Battalion

FIRST LIEUT. CHARLES O. GALLENKAMP - Historian Third Battalion

FIRST LIEUT. LLOYD H. BENNING - Historian Headquarters Company

FIRST LIEUT. HAROLD F. BROWN - Historian Supply Company

FIRST LIEUT. MORTON S. BAILEY -

SECOND LIEUT. WILLIAM J. LEE - Historians Machine Gun Company

Published By - THE 353RD INFANTRY SOCIETY

Copyright: Regimental Society, The 353rd Infantry - 1921

PRINTED AND BOUND BY THE EAGLE PRESS - WICHITA, KANSAS

http://www.kancoll.org